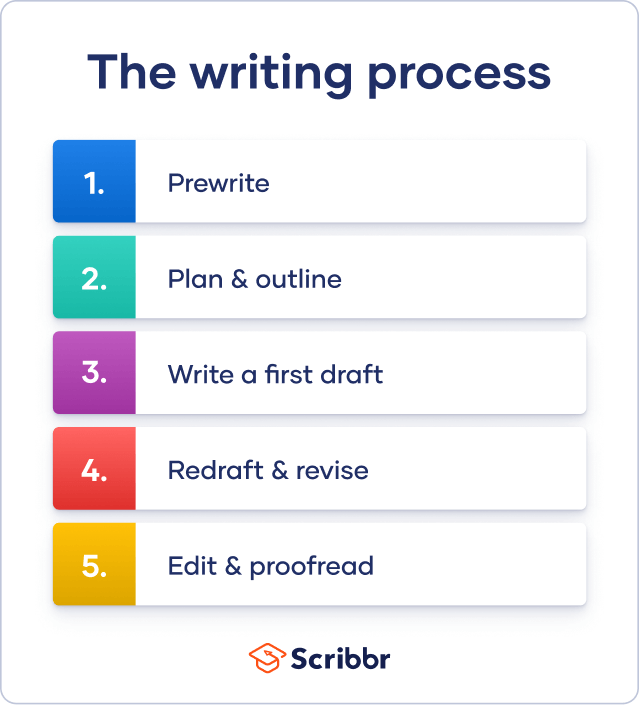

The Writing Process | 5 Steps with Examples & Tips

Good academic writing requires effective planning, drafting, and revision.

The writing process looks different for everyone, but there are five basic steps that will help you structure your time when writing any kind of text.

Step 1: Prewriting

Before you start writing, you need to decide exactly what you’ll write about and do the necessary research.

Coming up with a topic

If you have to come up with your own topic for an assignment, think of what you’ve covered in class—is there a particular area that intrigued, interested, or even confused you? Topics that left you with additional questions are perfect, as these are questions you can explore in your writing.

The scope of your topics depends on what type of text you’re writing—for example, an essay, a research paper or a dissertation. Don’t pick anything too ambitious to cover within the word count, or too limited for you to find much to say.

Narrow down your idea to a specific argument or question. For example, an appropriate topic for an essay might be narrowed down like this:

Doing the research

Once you know your topic, it’s time to search for relevant sources and gather the information you need. This process varies according to your field of study and the scope of the assignment. It might involve:

- Searching for primary and secondary sources.

- Reading the relevant texts closely (e.g. for literary analysis).

- Collecting data using relevant research methods (e.g. experiments, interviews or surveys)

From a writing perspective, the important thing is to take plenty of notes while you do the research. Keep track of the titles, authors, publication dates, and relevant quotations from your sources; the data you gathered; and your initial analysis or interpretation of the questions you’re addressing.

Step 2: Planning and outlining

Especially in academic writing, it’s important to use a logical structure to convey information effectively. It’s far better to plan this out in advance than to try to work out your structure once you’ve already begun writing.

Creating an essay outline is a useful way to plan out your structure before you start writing. This should help you work out the main ideas you want to focus on and how you’ll organize them. The outline doesn’t have to be final—it’s okay if your structure changes throughout the writing process.

Use bullet points or numbering to make your structure clear at a glance. Even for a short text that won’t use headings, it’s useful to summarize what you’ll discuss in each paragraph.

An outline for a literary analysis essay might look something like this:

- Introduction

- Describe the theatricality of Austen’s works

- Outline the role theater plays in Mansfield Park

- Introduce the research question: How does Austen use theater to express the characters’ morality in Mansfield Park?

- The frivolous acting scheme

- Discuss Austen’s depiction of the performance at the end of the first volume

- Discuss how Sir Bertram reacts to the acting scheme

- Stage directions

- Introduce Austen’s use of stage direction–like details during dialogue

- Explore how these are deployed to show the characters’ self-absorption

- The performance of morals

- Discuss Austen’s description of Maria and Julia’s relationship as polite but affectionless

- Compare Mrs. Norris’s self-conceit as charitable despite her idleness

- Conclusion

- Summarize the three themes: The acting scheme, stage directions, and the performance of morals

- Answer the research question

- Indicate areas for further study

Step 3: Writing a first draft

Once you have a clear idea of your structure, it’s time to produce a full first draft.

This process can be quite non-linear. For example, it’s reasonable to begin writing with the main body of the text, saving the introduction for later once you have a clearer idea of the text you’re introducing.

To give structure to your writing, use your outline as a framework. Make sure that each paragraph has a clear central focus that relates to your overall argument.

Hover over the parts of the example, from a literary analysis essay on Mansfield Park, to see how a paragraph is constructed.

The character of Mrs. Norris provides another example of the performance of morals in Mansfield Park. Early in the novel, she is described in scathing terms as one who knows “how to dictate liberality to others: but her love of money was equal to her love of directing” (p. 7). This hypocrisy does not interfere with her self-conceit as “the most liberal-minded sister and aunt in the world” (p. 7). Mrs. Norris is strongly concerned with appearing charitable, but unwilling to make any personal sacrifices to accomplish this. Instead, she stage-manages the charitable actions of others, never acknowledging that her schemes do not put her own time or money on the line. In this way, Austen again shows us a character whose morally upright behavior is fundamentally a performance—for whom the goal of doing good is less important than the goal of seeming good.

When you move onto a different topic, start a new paragraph. Use appropriate transition words and phrases to show the connections between your ideas.

The goal at this stage is to get a draft completed, not to make everything perfect as you go along. Once you have a full draft in front of you, you’ll have a clearer idea of where improvement is needed.

Give yourself a first draft deadline that leaves you a reasonable length of time to revise, edit, and proofread before the final deadline. For a longer text like a dissertation, you and your supervisor might agree on deadlines for individual chapters.

Step 4: Redrafting and revising

Now it’s time to look critically at your first draft and find potential areas for improvement. Redrafting means substantially adding or removing content, while revising involves making changes to structure and reformulating arguments.

Evaluating the first draft

It can be difficult to look objectively at your own writing. Your perspective might be positively or negatively biased—especially if you try to assess your work shortly after finishing it.

It’s best to leave your work alone for at least a day or two after completing the first draft. Come back after a break to evaluate it with fresh eyes; you’ll spot things you wouldn’t have otherwise.

When evaluating your writing at this stage, you’re mainly looking for larger issues such as changes to your arguments or structure. Starting with bigger concerns saves you time—there’s no point perfecting the grammar of something you end up cutting out anyway.

Right now, you’re looking for:

- Arguments that are unclear or illogical.

- Areas where information would be better presented in a different order.

- Passages where additional information or explanation is needed.

- Passages that are irrelevant to your overall argument.

For example, in our paper on Mansfield Park, we might realize the argument would be stronger with more direct consideration of the protagonist Fanny Price, and decide to try to find space for this in paragraph IV.

For some assignments, you’ll receive feedback on your first draft from a supervisor or peer. Be sure to pay close attention to what they tell you, as their advice will usually give you a clearer sense of which aspects of your text need improvement.

Redrafting and revising

Once you’ve decided where changes are needed, make the big changes first, as these are likely to have knock-on effects on the rest. Depending on what your text needs, this step might involve:

- Making changes to your overall argument.

- Reordering the text.

- Cutting parts of the text.

- Adding new text.

You can go back and forth between writing, redrafting and revising several times until you have a final draft that you’re happy with.

Think about what changes you can realistically accomplish in the time you have. If you are running low on time, you don’t want to leave your text in a messy state halfway through redrafting, so make sure to prioritize the most important changes.

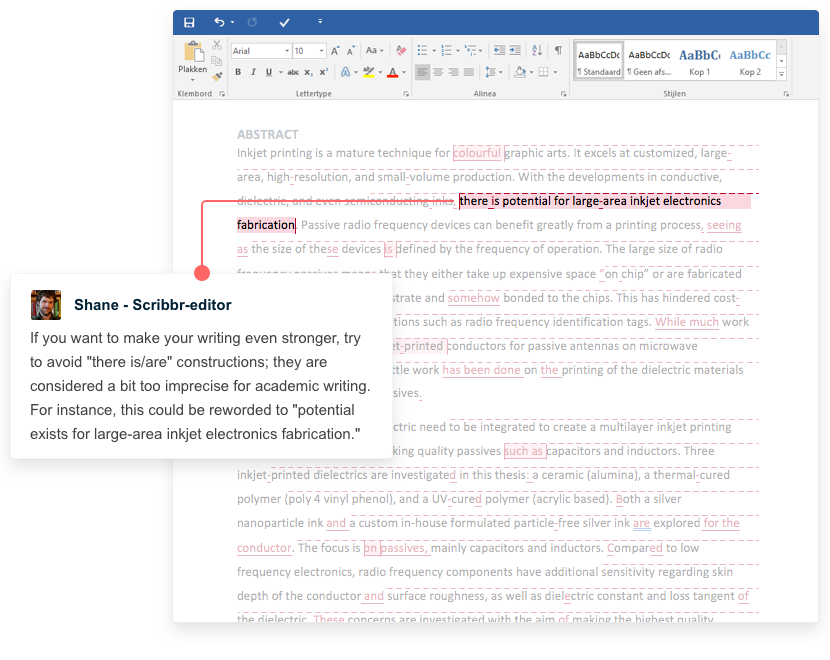

Step 5: Editing and proofreading

Editing focuses on local concerns like clarity and sentence structure. Proofreading involves reading the text closely to remove typos and ensure stylistic consistency.

Editing for grammar and clarity

When editing, you want to ensure your text is clear, concise, and grammatically correct. You’re looking out for:

- Grammatical errors.

- Ambiguous phrasings.

- Redundancy and repetition.

In your initial draft, it’s common to end up with a lot of sentences that are poorly formulated. Look critically at where your meaning could be conveyed in a more effective way or in fewer words, and watch out for common sentence structure mistakes like run-on sentences and sentence fragments:

Proofreading for small mistakes and typos

When proofreading, first look out for typos in your text:

- Spelling errors.

- Missing words.

- Confused word choices.

- Punctuation errors.

- Missing or excess spaces.

Use your word processor’s built-in spell check, but don’t expect to find 100% of issues in this way. Read through your text line by line, watching out for problem areas highlighted by the software but also for any other issues it might have missed.

For example, in the following phrase we notice several errors:

- Mary Crawfords character is a complicate one and her relationships with Fanny and Edmund undergoes several transformations through out the novel.

- Mary Crawford’s character is a complicated one, and her relationships with both Fanny and Edmund undergo several transformations throughout the novel.

Proofreading for stylistic consistency

There are several issues in academic writing where you can choose between multiple different standards. For example:

- Whether you use the serial comma.

- Whether you use American or British spellings and punctuation.

- Where you use numerals vs. words for numbers.

- How you capitalize your titles and headings.

Unless you’re given specific guidance on these issues, it’s your choice which standards you follow. The important thing is to consistently follow one standard for each issue. For example, don’t use a mixture of American and British spellings in your paper.

Additionally, you will probably be provided with specific guidelines for issues related to format (how your text is presented on the page) and citations (how you acknowledge your sources). Always follow these instructions carefully.

Frequently asked questions about the writing process

- What’s the difference between revising, proofreading, and editing?

-

Revising, proofreading, and editing are different stages of the writing process.

- Revising is making structural and logical changes to your text—reformulating arguments and reordering information.

- Editing refers to making more local changes to things like sentence structure and phrasing to make sure your meaning is conveyed clearly and concisely.

- Proofreading involves looking at the text closely, line by line, to spot any typos and issues with consistency and correct them.

- How can I get better at proofreading?

-

Whether you’re publishing a blog, submitting a research paper, or even just writing an important email, there are a few techniques you can use to make sure it’s error-free:

- Take a break: Set your work aside for at least a few hours so that you can look at it with fresh eyes.

- Proofread a printout: Staring at a screen for too long can cause fatigue – sit down with a pen and paper to check the final version.

- Use digital shortcuts: Take note of any recurring mistakes (for example, misspelling a particular word, switching between US and UK English, or inconsistently capitalizing a term), and use Find and Replace to fix it throughout the document.

If you want to be confident that an important text is error-free, it might be worth choosing a professional proofreading service instead.

- How can I edit a paper that is over the word limit?

-

If you’ve gone over the word limit set for your assignment, shorten your sentences and cut repetition and redundancy during the editing process. If you use a lot of long quotes, consider shortening them to just the essentials.

If you need to remove a lot of words, you may have to cut certain passages. Remember that everything in the text should be there to support your argument; look for any information that’s not essential to your point and remove it.

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

This Scribbr articleCaulfield, J. (April 23, 2022). The Writing Process | 5 Steps with Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved October 19, 2022, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-writing/writing-process/